- Home

- Daniel Pennac

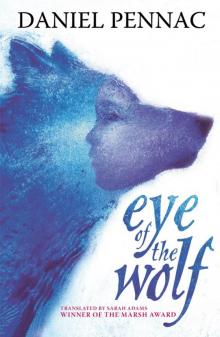

The Eye of the Wolf Page 3

The Eye of the Wolf Read online

Page 3

Here we are, Blue Wolf; this is where my first memory took place!

II

It’s a terrifying night. A moonless African night. You’d think the sun had never shone on Earth. And there’s such a din. Panicked cries, flashes of light splitting the darkness in every direction, followed by a series of explosions: just like the night when Blue Wolf was captured. Then comes the crackling of flames. Black shadows are cast against the walls in the red glow. This is war, or something close to it. Everywhere you look, fires are blazing and houses are crashing down…

“Toa! Toa!” a woman calls out as she runs. She’s carrying something in her arms and shouting out to a man who’s sidling along the walls. He’s leading an enormous camel by the reins.

“Toa the trader, please listen to me!”

“This is hardly the moment for idle chat.”

“I haven’t come to chat. It’s for the child’s sake, Toa. Take this child and lead him far away from here. He doesn’t have a mother any more.” She holds out the bundle in her arms.

“What do you want me to do with such a tiny child? He’ll just drink all my water.”

The flames suddenly leap out of a neighbouring window. Toa can smell his moustache getting singed. “Oh, Africa! Curse Africa!”

“I’m begging you, Toa, save the child. When he’s older he’ll become a storyteller; he’ll tell stories to make people dream.”

“I’ve no use for dreams; I’ve got enough problems on my hands with this idiot of a camel who does nothing but dream from morning to night.”

The camel, who has been making his way through the scene of destruction as calmly as if it was an oasis, comes to a complete standstill.

“Toa!” shouts the woman. “I’ll pay you.”

“I’m not interested. Are you going to get a move on?”

“Lots of money, Toa, lots!”

“Stupid camel, every time I tell him he’s an idiot, he refuses to budge. How much money?”

“Everything I’ve got.”

“Everything?”

“Absolutely everything!”

III

Day breaks over a completely different landscape. Blue Wolf can’t believe his eyes. Snow! There’s not a tree or a rock or a single blade of grass in sight. Just snow. And blue sky. Big hills of snow, as far as the eye can see. A strange, yellow kind of snow that creaks and crunches with every step, and slides in patches like the snow in Alaska. In the middle of the sky there’s a white sun so bright it blinds people, and it makes Toa the trader drip with sweat.

“Curse this desert! Curse this sand! Will it never end?” Toa is bent double as he walks. He leads the camel by the reins, and swears between his teeth. “Oh, Africa! Curse Africa!”

The camel doesn’t listen to him. He moves on dreamily. Actually, he’s not a camel – he’s a dromedary. He’s only got one hump. It’s mind-boggling what Toa has managed to pile onto his back! Saucepans, boilers, coffee grinders, shoes, paraffin lamps, rush-stools: he’s like a walking ironmonger’s shop, rattling with every bump of his hump. And up there, right on top of the heap, sitting bolt upright and wrapped in a Bedouin coat, is the boy. He gazes into the distance.

There you are, thinks the wolf. I was worried that crook would desert you.

Blue Wolf has every reason to be concerned. Many years have slipped by since that dreadful night, and Toa the trader has tried to abandon the boy many times. He always goes about it in the same way. On certain mornings, when he’s in a particularly foul mood (business is bad; the watering place has run dry; it’s been a cold night … there’s always an excuse), he gets up without making a noise, rolls up his brown wool tent and whispers in the ear of his dozing camel, “Let’s get going, camel. Up you get. We’re off.”

The boy pretends to be asleep. He knows what’ll happen next.

“Are you coming then?” Toa the trader pulls on the bridle while the dromedary looks at him and chews an old thistle. “Are you going to get up, or what?”

No. The dromedary stays slumped on his knees. At this point Toa always brandishes a big knobbly stick. “Is this what you want?” But when the dromedary rolls back his chops and bares his big flat yellow teeth, the stick always falls to the ground.

I’m not leaving without the boy. That’s what the dromedary is saying behind his silence and his stillness and his calm gaze.

So Toa goes over to wake up the boy with a sharp slap. “Come on, get up! I’m late enough as it is because of you. Climb up there and don’t move an inch.”

The dromedary won’t allow anyone else on his back. So the boy always rides up above and Toa the trader stays down below, walking on foot through the burning sand.

“Good morning, Sand Flea, did you sleep well?”

“Sound as Africa! And you, Saucepans, did you have a good night?” (The boy’s nickname for the dromedary is Saucepans.)

“Slept like a log, and I had very interesting dreams.”

“Right, are we off?”

“Let’s go.”

Saucepans unfolds his legs and stands up against the orange sky.

The sun rises. Toa the trader swears and spits and curses Africa. The dromedary and the boy chuckle. They learned how to laugh on the inside a long time ago. Seen from the outside, they are both as smooth and serious as sand dunes.

IV

So that was the first chapter of his life. Even if he’d scoured all of Africa, Toa the trader would never have found a boy faster at loading and unloading the dromedary. He’d never have found someone better at arranging the merchandise in front of the Bedouin tents, someone who understood the camels more deeply, or, most importantly, someone who could tell such incredible stories at night, around the fires, when the Sahara becomes as cold as a desert of ice and you feel all alone in the world.

“He tells them well, doesn’t he?”

“He’s a good storyteller, isn’t he?”

“It’s the way he tells them!”

His stories attracted customers from the nomad camps. Toa was happy.

“Eh! Toa, what do you call your boy?”

“Haven’t had time to give him a name – too busy working.”

The nomads didn’t like Toa the trader. “Toa, you don’t deserve this boy.” They would offer the boy a seat near the brazier, feed him with boiling tea, dates and milk curds (they thought he was too thin), and they would say, “Tell us a story.”

So the boy would tell them stories he had made up in his head while he was sitting on Saucepans’ hump. Or else he would tell them the dromedary’s dreams, because the dromedary dreamed every night and sometimes he even dreamed while he was walking in the sunshine. They were stories about Yellow Africa, about the Sahara, about an Africa filled with sands and sunshine and solitude and scorpions and silence. And when the caravans set out again under the blazing sky, those who had listened to the boy’s stories saw a different Africa from high up on their camels. In this new Africa the sand was gentle underfoot, the sun was a fountain, and they were no longer alone: the young boy’s voice followed them wherever they went in the desert.

“Africa!”

It was during one of these nights that an old Tuareg chief, who was at least a hundred and fifty years old, declared, “Toa, we’ll call this boy Africa!”

Toa stayed back and sat on his coat while Africa was telling his stories. But he would get up at the end of each story and hold out a tin bowl to collect bronze coins or old notes.

“He’s even got the nerve to charge us for the boy’s stories.”

“Toa the trader, you’d sell yourself if someone was willing to pay for you.”

“I’m a trader,” Toa would grumble. “It’s my job to sell things.”

They were right when they said that Toa would sell everything he had. And one fine morning he did just that.

It happened in a town in the south where the desert sands run out. It’s a different Africa. Grey. With burning stones and thorny bushes and, further south still, great plains of

dried plants.

“Wait here for me,” Toa had ordered. “Guard the tent.”

And he had disappeared off into the town, leading his camel by the reins. Africa was no longer frightened of being abandoned. He knew that Saucepans would never leave town without him.

But when Toa returned, he was alone. “I’ve sold the camel.”

“What do you mean? You’ve sold Saucepans? Who to?”

“None of your business.” There was a strange glint in his eye. “Oh, and by the way, I’ve sold you too.” And he added, “You’re a shepherd now.”

V

After Toa left, Africa spent hours searching for Saucepans. But it was no use.

He can’t have left town; he wouldn’t have taken a single step without me. He promised!

He questioned passers-by.

“Little one, there are two thousand camels sold here every day,” they replied.

He asked children his own age. “You wouldn’t have seen a dromedary who dreams, by any chance?”

The children laughed. “All dromedaries dream.”

He even interrogated the camels themselves. “A dromedary who’s as tall as a sand dune!”

The camels looked down on him from a great height. “There are no dumpy dromedaries in our crowd, boy, only beautiful beasts…”

And of course, he also approached the camel buyers. “A handsome dromedary the colour of sand, sold by Toa the trader…”

“How much?” the buyers asked, because they were only interested in prices.

This carried on until the king of goats lost his temper. “Now, listen up, Africa! You’re not here to hunt for a dromedary; your job is to protect my flocks.”

Toa had sold Africa to the king of goats. The king of goats wasn’t a cruel master, but he loved his flocks more than anything in the world. His curly white hair was like sheep’s wool; he ate nothing but goat’s cheese and drank nothing but ewe’s milk; and when he bleated his words the long hairs of his goatee beard wobbled. He lived in a tent instead of a house, to remind him of the times when he tended the flocks himself, and he never got up off the vast curly black sheepskin that was his bed.

“Yes, I’m too old now. Otherwise I wouldn’t need a shepherd.”

If a ewe fell ill or a ram broke his leg or a goat disappeared, he sacked his shepherds on the spot.

“Do I make myself clear, Africa?”

The boy nodded.

“Right, sit down and listen.” The king of goats held out a large piece of cheese and a bowl of milk that was still warm, and he taught him how to be a shepherd.

Africa worked for the king of goats for two whole years. The inhabitants of Grey Africa couldn’t get over it. “The old man doesn’t normally keep a shepherd for more than two weeks. What’s your secret?”

But Africa didn’t have any secret. He was a good shepherd, and that was all there was to it. He had grasped a basic principle: flocks don’t have enemies. If a lion or a cheetah eats a goat from time to time, it’s because he’s hungry. Africa had explained this to the king of goats.

“King, if you don’t want the lions to attack your flocks, you’ll have to give them something else to eat.”

“Feed the lions?”

The king of goats twiddled his beard. “All right, Africa, perhaps it’s not such a bad idea.”

So, wherever Africa led the goats to pasture, he laid out large chunks of meat he’d brought with him from the town. “Here’s your share, Lion, so please leave my goats alone.”

The old lion of Grey Africa took his time sniffing the chunks of meat. “You’re a funny one, Shepherd, you really are a funny one.” And then he tucked in.

Africa held a longer conversation with the cheetah. One evening when the cheetah was creeping cautiously towards the flock, Africa said, “It’s no good pretending to be a snake, Cheetah – I heard you.”

The astonished cheetah poked his head above the dry grass. “How did you know I was here, Shepherd? No one ever hears me!”

“I come from Yellow Africa. There’s so much silence back there it sharpens our ears. Listen – I can hear two fleas arguing on your shoulder.”

With one snap of his teeth the cheetah devoured both fleas.

“Right,” said Africa, “I need to talk to you.”

The cheetah was impressed so he sat down and listened.

“You’re a good hunter, Cheetah. You can run faster than all the other animals, and you can see further too. Those are the skills a shepherd needs.”

There was silence. They heard an elephant trumpeting in the distance; then came the sound of shots ringing out.

“Foreign hunters…” murmured Africa.

“Yes, they’re back,” said the cheetah. “I saw them yesterday.”

They were sad and silent for a while.

“Cheetah, what about teaming up with me as a shepherd?”

“What’s in it for me?”

Africa stared at the cheetah for a long time. Two old tears had left black stains that went right down to the corners of his mouth.

“You need a friend, Cheetah, and so do I.”

And very soon Africa and the cheetah were inseparable.

VI

When the grazing areas were too far apart, the youngest goats couldn’t keep up with the flock. They tired easily. They would fall behind and the hyenas, who were never far off, would lick their chops and cackle. The cheetah was fed up because he had to keep going backwards and forwards to fend off the hyenas. The most vulnerable kids were also very rare and beautiful; they were a special breed that the king of goats called “my Abyssinian doves”. He spent sleepless nights worrying something might happen to them.

“King, I’ve had an idea about how to protect your doves. We should leave the youngest ones behind,” Africa explained.

The king of goats plucked three hairs out of his beard. “Leave them behind where they’ll be unprotected! Are you out of your mind? What about the hyenas?”

“That’s just the point. If I leave the kids in the biggest thorny shrubs, the hyenas won’t touch them.”

The king of goats closed his eyes and thought quickly. Let’s see … all goats graze on thorns, they’ve got mouths made to grind nails, they’ve got thorn-proof fur, and if there’s one thing hyenas can’t stand it’s thorns. There’s no doubt about it – it’s a great idea.

Turning to Africa again, he stroked his beard and asked, “Tell me, Africa, why didn’t I have this idea before you did?”

Africa looked into the old man’s pale, worn-out eyes and replied gently, “Because I’m the shepherd now. And you’re the king.”

The hyena’s head contemplating a thorny shrub was a sight to see.

“It’s just not fair, Africa, to have a goat right under my nose, and an Abyssinian dove at that! What a temptation! It’s downright cruel of you.” She was drooling so much that flowers could have sprung up between her paws.

Africa patted her on the forehead. “When I come back, I’ll bring you the old lion’s leftovers. Lions are just like rich people – they never finish their food.”

The cheetah didn’t like the smell of the hyena and he frowned. “Shepherd, you shouldn’t talk to that.”

“I talk to everyone.”

“You’re making a mistake. I don’t trust that one little bit.”

The flock started moving again. The cheetah cast a final scornful glance at the hyena before announcing to Africa, “Not that it matters anyway. While I’m alive, no one will ever eat one of your goats.”

The days turned to months and the flock prospered. The king of goats slept peacefully at night. Everyone was happy, including the hyena, who made a feast of the lion’s leftovers. She even claimed to hover around the thorny shrubs in order to protect the Abyssinian doves. The cheetah would shake his head and look at the sky.

“It’s the honest truth!” the hyena insisted. “If anything happened to the doves, Shepherd, I’d be the first to let you know!”

The little shep

herd boy’s fame spread throughout Grey Africa. He was very popular. When Africa lit his fires in the evening, a host of black shadows soon slid up to him. These weren’t the shadows of robbers or ravenous animals. It was a crowd of men and beasts that gathered to hear the stories of Africa, shepherd boy to the king of goats. He told them about another Africa, Yellow Africa. He told them about the dreams of a dromedary called Saucepans, who had mysteriously disappeared. And he spun them tales of Grey Africa too, which he knew better than they did, even though he wasn’t born there.

“He tells them well, doesn’t he?”

“He’s a good storyteller, isn’t he?”

“It’s the way he tells them!”

And when dawn came and everyone headed off in different directions, they felt they were still somehow together.

One day the grey gorilla of the swamps interrupted a story. “Did you know there’s another Africa, Shepherd? Green Africa, filled with trees as high and puffy as clouds. I’ve got a cousin who lives there; he’s a strapping fellow with a pointy skull!”

Green Africa? No one was very convinced. But they didn’t want to argue with the grey gorilla of the swamps…

Life is strange… Someone tells you about something you didn’t even know existed, something unimaginable, something you can’t bring yourself to believe in, and the words are hardly out of their mouth before you find out all about it for yourself.

Green Africa… It was a place the boy would soon be very familiar with.

VII

One night Africa was telling a story and the animals were all listening, when the cheetah suddenly whistled. “Sshh!”

They could hear the hyena laughing far off in the distance. But it wasn’t her usual laugh; it was a furious cackling…

“Something’s happened to the Abyssinian doves!” The cheetah leaped to his feet. “I’m off! Meet me over there, Shepherd, and bring the flock with you.” Then, just before disappearing, “I told you never to trust that.”

The Eye of the Wolf

The Eye of the Wolf