- Home

- Daniel Pennac

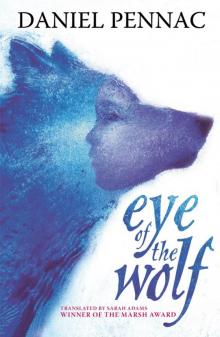

The Eye of the Wolf

The Eye of the Wolf Read online

Contents

How They Met

I

II

III

The Eye of the Wolf

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

The Human Eye

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

The Other World

I

II

Pour Alice, princesse Li Tsou,

et Louitou, type formidab’

How They Met

I

The boy standing in front of the wolf’s cage doesn’t move a muscle. The wolf paces backwards and forwards. He walks the length of the enclosure and back again without stopping.

He’s starting to get on my nerves, the wolf thinks to himself. For the last two hours the boy has been standing in front of the wire fencing, as still as a frozen tree, watching the wolf walking.

What does he want from me? the wolf wonders. The boy makes him feel curious. He’s not worried (because wolves aren’t afraid of anything), just curious. What does he want?

The other children jump and run about, shout and burst into tears, stick their tongues out at the wolf and hide their heads in their mums’ skirts. Then they make silly faces in front of the gorilla’s cage, or roar at the lion as he whips the air with his tail. But this boy is different. He stands there silently, without moving a muscle. Only his eyes shift. They follow the wolf as he paces the length of his wire fencing.

What’s your problem? Haven’t you ever seen a wolf before?

The wolf only sees the boy every other time he passes him. That’s because the wolf only has one eye. He lost the other one ten years ago in a fight against humans, the day he was captured. So on his outward journey (if you can call it a journey) the wolf sees the zoo with all its cages, the children making faces and, standing in the middle of it all, the boy who doesn’t move a muscle. On the return journey (if you can call it a journey) the wolf sees the inside of his enclosure. It’s an empty enclosure, because the she-wolf died last week. It’s a sad enclosure with a solitary rock and a dead tree. When the wolf turns round, there’s the boy again, breathing steadily, his white breath hanging in the cold air.

He’ll give up before I do, thinks the wolf, and he carries on walking. I’m more patient than he is, he adds. I’m the wolf.

II

But the first thing the wolf sees when he wakes up the next day is the boy, standing in exactly the same spot in front of his enclosure. The wolf nearly jumps out of his fur.

He can’t have spent the night here!

He calms down and begins to pace again, as if it is nothing out of the ordinary.

The wolf’s been walking for an hour now. And the boy’s eyes have been following him for an hour. The wolf’s blue fur brushes against the wire fencing. His muscles ripple beneath his winter coat. The blue wolf keeps on walking as if nothing will ever stop him. As if he’s on his way back home to Alaska, where he comes from. The metal plaque fixed to his cage reads ALASKAN WOLF. And there’s a map of the Far North, with an area marked in red: ALASKAN WOLF, BARREN LANDS.

His paws don’t make a sound when they touch the ground. He moves from one end of the enclosure to the other, like a silent pendulum inside a grandfather clock. The boy’s eyes move slowly, as if he’s following a game of tennis in slow motion.

Does he really think I’m that interesting?

The wolf frowns. The bristles on his muzzle stand on end. He’s annoyed with himself for asking so many questions. He swore not to have anything more to do with human beings. He’s been true to his word for ten years now: he hasn’t thought about human beings once, or even glanced at them. He has cut himself off completely. He doesn’t look at the kids making silly faces in front of his cage, or the zookeeper throwing him his meat from a distance, or the artists drawing him on Sundays, or the stupid mums showing him to their toddlers and squawking, “Look at the big bad wolf! He’ll gobble you up if you’re naughty!” He doesn’t look at any of them.

“Not even the best human beings are worth bothering about.” That’s what Black Flame, the wolf’s mother, always used to say.

Sometimes the wolf would take a break from pacing. Up until last week, that is. He and the she-wolf would sit facing the visitors. It was as if they couldn’t see them. He and the she-wolf would stare straight ahead. They stared straight through them. It made the visitors feel like they didn’t even exist. It was spooky.

“What are they looking at in that strange way?”

“What can they see?”

But then the she-wolf, who was grey and white like a snow partridge, died. The wolf hasn’t stopped moving since. He walks from morning to evening, and leaves his meat to freeze on the ground. Outside, straight as the letter i (imagine the dot is his white breath hanging in the air), the boy watches him.

If that’s the way he wants it, that’s his problem, the wolf decides. And he stops thinking about the boy altogether.

III

But the next day the boy is there again. And the following day. And the day after that. Until the wolf can’t help thinking about him again. Who is he? What does he want from me? Doesn’t he have anything to do all day? Doesn’t he have work to do? Or school to go to? Hasn’t he got any friends? Or parents? Or relatives?

So many questions slow his pace; his legs feel heavy. He’s not worn out yet, but he might be soon. Unbelievable! thinks the wolf.

At least the zoo will be closed tomorrow. Once a month there’s a special day when the zookeepers check on the animals’ health and repair their cages. No visitors are allowed.

That’ll get him off my back.

Wrong again. The next day, just like all the other days, the boy is there. He seems to be more present than ever – all alone in front of the enclosure, all alone in an empty zoo.

Oh, no, groans the wolf. But that’s the way it is.

The wolf is starting to feel worn out now. The boy’s stare seems to weigh a ton. All right, thinks the wolf. You’ve asked for it! And suddenly he stops walking. He sits bolt upright opposite the boy. And he starts staring back. He doesn’t look through him. It’s a real stare, a fixed stare.

So now they’re opposite each other.

And they just keep on staring.

There isn’t a single visitor in the zoo. The vets haven’t arrived yet. The lions haven’t come out of their lair. The birds are asleep under their feathers. It’s a day of rest for everyone. Even the monkeys have stopped making mischief. They hang from the branches like sleeping bats.

There’s just the boy.

And the wolf with the blue fur.

So you want to stare at me? Fine! I’ll stare at you too. And we’ll soon see…

But there’s something bothering the wolf. A silly detail. He’s only got one eye and the boy’s got two. The wolf doesn’t know which of the boy’s eyes to stare into. He hesitates. His single eye jumps: right-left, left-right. The boy’s eyes don’t flinch. He doesn’t flutter an eyelash. The wolf feels extremely uneasy. He won’t turn his head away for the whole world. And there’s no question of starting to pace again. His eye begins to lose control. Soon, across the scar of his dead eye, a tear appears. Not because he’s sad, but out of a sense of helplessness and anger.

So the boy does something strange that calms the wolf and makes him feel more at ease. The boy closes an eye.

Now they’re looking into each other’s eye, in a zoo that’s silent and empty, and they’ve got all the time in the world.

The Eye of t

he Wolf

I

The wolf’s yellow eye is large and round, with a black pupil in the middle. And it never blinks. The boy could be watching a candle flame in the dark. All he can see is the eye: the trees, the zoo and the enclosure have disappeared. All that’s left is the eye of the wolf. It grows fatter and rounder, like a harvest moon in an empty sky. The pupil in the middle grows darker, and he can make out small coloured flecks in the yellow-brown iris – a speck of blue here, like frozen water below the sky; a glimmer of gold there, shiny as straw.

But what really matters is the pupil. The black pupil. You wanted to stare at me, it seems to be saying, so go ahead, stare at me! It sparkles so brightly, it’s scary. Like a flame.

That’s what it is, thinks the boy, a black flame! Then he answers, “All right, Black Flame, I’m staring at you and I’m not frightened.”

The pupil blazes like fire as it fills the eye. But no matter how fat it gets, the boy never looks away. When everything has become pitch black, he discovers what nobody has ever seen in the wolf’s eye before: the pupil is alive. There, staring and growling at the boy, is a black she-wolf snuggled up with her cubs. She doesn’t move, but you can tell she’s tense as a thunderstorm under her shiny fur. Her gums are pulled back to expose her dazzling fangs; her paws are twitching. She’s ready to pounce. She’d swallow a small boy like him in a single mouthful.

“So you’re really not frightened?”

That’s right. The boy stays where he is. He doesn’t look away. Slowly Black Flame allows her muscles to relax. After a while she whispers between her fangs, “Fine, we’ll make a deal. You can stare as much as you like, if that’s the way you want it, but don’t disturb me while I’m teaching the little ones – is that clear?” And, without sparing the boy another thought, she casts a careful eye over the seven fluffy cubs asleep around her. They form a red-tinged halo.

The iris, thinks the boy, the iris around the pupil…

Five of the cubs are exactly the same rust-red colour as the iris. The sixth one has blue-red fur, as blue as frozen water under a clear sky. He’s called Blue Wolf. And the seventh, a little yellow she-wolf, is like a ray of gold. It makes your eyes crinkle just to look at her. Her brothers call her Shiny Straw.

All around them lies the snow. It stretches as far as the hills on the horizon. The silent snow of Alaska in the Far North.

Black Flame’s voice rises solemnly out of the white silence. “Children, today I’m going to talk to you about human beings.”

II

“Humans?”

“Again?”

“Boring!”

“You’re always telling us stories about humans.”

“We’ve heard enough!”

“We’re not babies!”

“Why don’t you tell us about caribou, or snow rabbits, or duck-hunting?”

“Yes, Black Flame, tell us a hunting story.”

“Wolves are hunters, so give us a hunting story.”

But Shiny Straw’s cries can be heard above all the rest. “No, I want a real story about humans, a scary story. Please, Mum, please, I love human stories!”

Only Blue Wolf keeps quiet. He’s not much of a talker. In fact, he’s rather serious. A bit sad you might say. Even his brothers think he’s too serious. But on the rare occasions when he speaks, everyone listens. He’s as wise as an old wolf with battle scars.

Picture the scene: the five Redheads are scrapping – going for each other’s throats, jumping on each other’s backs, snapping at each other’s legs, chasing their own tails in crazy circles … it’s mayhem. Shiny Straw cheers them on in her high-pitched voice, jumping up and down on the spot like a frog in spring. And silver glints of snow fly all around them.

Black Flame just lets them get on with it. They might as well enjoy themselves while they can; they’ll find out how tough a wolf’s life is soon enough. She glances at Blue Wolf, the only one of her children who never fools around. The spitting image of his father. This thought makes her feel proud and sad at the same time because Great Wolf, his father, is dead.

Too serious, thinks Black Flame. Too much of a worrier… Too much of a wolf…

“Listen!” Blue Wolf is sitting as still as a rock, his front legs stiff and his ears pricked up. “Listen!”

The scrapping stops straight away. The snow begins to settle again around the cubs. They can’t hear anything to begin with. The Redheads strain their furry ears, but all they can make out is the sudden moaning of the wind, like a frozen tongue licking them.

And then, all of a sudden, the long, modulated howl of a wolf is heard behind the wind, and it speaks volumes.

“It’s Grey Cousin,” whispers one of the Redheads.

“What’s he saying?”

Black Flame glances quickly at Blue Wolf. Both of them know what Grey Cousin is telling them from the hilltop where he’s standing guard.

Men! A band of hunters… Trying to track them down. The same band as last time.

“The game’s over now, children. Get ready – we’re leaving!”

III

So was that how you spent your childhood, Blue Wolf: trying to escape from bands of hunters?

Yes, it was. We settled in a peaceful valley surrounded by hills that Grey Cousin thought no human could climb over. We stayed there for a week or two, but then we had to move on again. The men refused to give up. The same band had been on our family’s trail for two moons. They’d already got Great Wolf, our father – not without a struggle, but they got him in the end.

So we made a hasty escape. We walked in single file. Black Flame led the procession, followed by me, Blue Wolf. Then came Shiny Straw and the Redheads. And, bringing up the rear, Grey Cousin wiped away the footprints with his tail. We never left any marks. We vanished completely as we pushed on deeper into the north. It grew colder. The snow turned to ice; the rocks became sharp as knives. But the men still managed to track us down.

They were always on our heels. No obstacle was too great for them. Those men… Human beings…

At night they slept in foxes’ dens. (Foxes are always willing to lend their dens to wolves. They do it for food, because they’re too lazy to hunt for themselves.) Grey Cousin would keep watch outside, sitting on a rock overlooking the valley. Blue Wolf would sleep at the entrance to the den. Right at the back, Black Flame would tell the little cubs stories until they fell asleep. They were human stories, of course. Because it was night-time and they were too tired to play any more, because they loved being scared and Black Flame was there to protect them, Shiny Straw and the Redheads listened.

Once upon a time…

It was always the same story about a clumsy cub and his aged grandmother:

Once upon a time there lived a cub who was so clumsy he’d never caught anything in his life. Even the oldest caribou ran too quickly for him, field mice got away from right under his nose, and ducks flew within a whisker of his muzzle. He couldn’t even catch his own tail! He was just too clumsy.

But he had to be good at something, didn’t he? Fortunately he had a granny who was very old. She was so old she couldn’t catch anything either. Her big sad eyes would watch the young wolves running. Her skin no longer quivered at the scent of game. Everybody felt sorry for her.

They left her behind in the lair when they went off hunting. Slowly she would do the tidying up, before washing herself with great care. She had a magnificent coat. It was silver, and it was all that remained of her youth. No other wolf had ever had such a beautiful coat. When she’d finished washing herself – it took her at least two hours – Granny would lie down at the entrance to the lair, with her muzzle between her paws, waiting for Clumsy to come back. It was Clumsy’s job to feed Granny. The haunch of the first caribou killed always went to Granny.

“Are you sure it’s not too heavy for you, Clumsy?”

“Of course not!”

“Make sure you don’t dawdle on the way back.”

“And don’t trip over y

our paws!”

“And steer clear of humans.”

And so on.

Clumsy had given up listening to all this advice. He knew what he was doing.

Until one day when—

“Until one day when what?” asked the Redheads, their big eyes dilated in the dark.

“When what? When what?” squeaked Shiny Straw with her tongue hanging out.

Black Flame’s voice came in a terrifying whisper:

Until one day when a man reached the lair before Clumsy did.

“And then what?”

“And then what? Go on… What happened next?”

The man killed Granny, stole her fur to make a coat, stole her ears to make a hat and turned her muzzle into a mask.

“And what happened after that?”

“You’ll find out when I tell you the rest tomorrow. It’s time for bed now, children.”

The cubs complained, but Black Flame was firm. Gradually drowsy sounds filled the lair. Blue Wolf always waited for this moment to ask his question. And he always asked the same thing.

“Was that a true story, Black Flame?”

Black Flame would pause and consider before giving the same strange reply. “Let’s just say, more true than not.”

IV

The seasons came and went, and the cubs grew into young wolves and skilful hunters. But they’d never seen a human being. Not close up, at any rate. They’d heard the noises humans make. On the day Great Wolf fought his battle against them, for example. They’d heard Great Wolf howling, and a man roaring with pain at fangs sunk into his backside. They’d heard the shouts of panic, the orders barked out, something that sounded like a clap of thunder and then … nothing. Great Wolf never came back.

So they found themselves on the run again.

They’d seen them from a distance. No sooner had they left a valley than the humans settled in. The valley would begin to smoke like a cauldron.

The Eye of the Wolf

The Eye of the Wolf